The Mark Morris Dance Group performs at BAM.

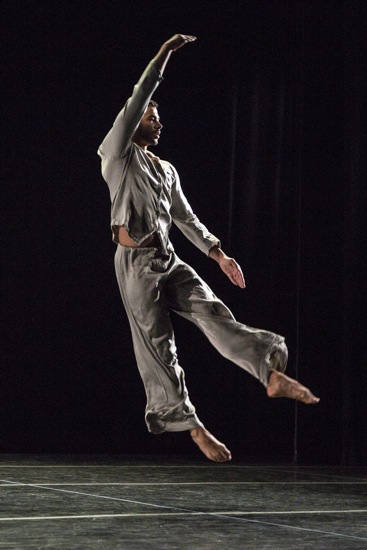

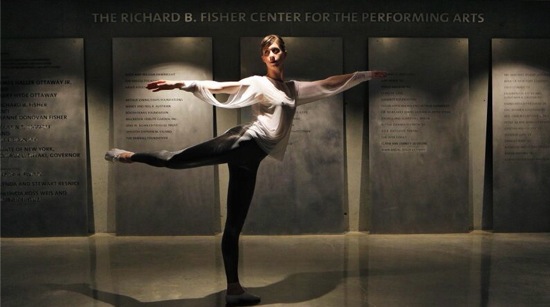

![Aaron Loux in Mark Morris's Pacifica. Photo: Hilary Schwab]()

A marvel: Aaron Loux in Mark Morris’s Pacific. Photo: Hilary Schwab

Was it George Balanchine who said he wanted us to see the music and hear the dancing when we were watching his ballets? Maybe he said only the first part of that. Mark Morris, I think, hopes for something similar when we see his choreography—not meaning that we should hear feet hit the floor, but that the dancers carry the music in their bodies, and if the music stops for some reason, but the dancers go on dancing, we might hear something like it in our heads.

I wish I knew what aspects of each musical composition that Morris works with influence his choreographic choices. Sometimes he follows the rhythm proper closely, sometimes the words of a song. But more often, he seems also to be guided by the music’s atmosphere, degree of density, instrumentation, history, and the ineffable images that creep into his brain when he listens to it.

The two new-to-New-York works that the Mark Morris Dance Group performed during its recent season at the Brooklyn Academy of Music have different origins. Spring, Spring, Spring is set to a recent arrangement of Igor Stravinsky’s masterpiece, The Rite of Spring. The 1913 ballet by Vaslav Nijinsky for which the music was written depicted a pagan spring ritual in which a virgin was chosen to dance herself to death in order to urge the earth to get busy being fertile. There were countless tales of the initial shocked reaction to the music’s thundering dissonances and the dancers’ pounding, unballetic movements. Since then, a slew of dances have been set to the score. All this history Morris had to deal with or disregard; he chose a stance closer to the disregard-entirely possibility.

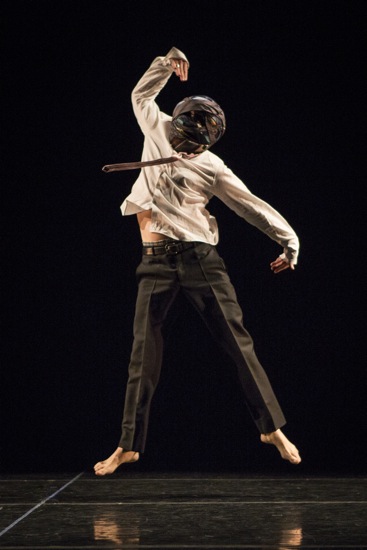

![Aaron Loux (L) and Dallas McMurray in Mark Morris's Whelm. Photo: Yi Chun Wu]()

Aaron Loux (L) and Dallas McMurray in Mark Morris’s Whelm. Photo: Yi Chun Wu

The other New York premiere, Whelm, is set to music not meant to be danced to: Claude Debussy’s impressionistic piano pieces “Des pas sur la neige,” “Etude pour les notes répétées,” and “La cathédrale engloutie.” The titles are suggestive: steps in the snow—soft, often unheard, yet leaving prints; a mythical Breton cathedral engulfed by the ocean. The repeated notes in the second piece are often spat out in staccato phrases marked off by pauses. And, unless Morris had a macabre dream and found music that enhanced it, he heard things in these works that inspired him to choreograph Whelm.

His title word can be defined as to overcome utterly, to submerge, to engulf, and you can divine these acts in the mysterious piece that Morris crafted for four dancers. You can’t even be sure what you’re seeing at the outset, thanks to Nick Kolin’s exceedingly dim light and the black costumes that Elizabeth Kurtzman has designed. A path of light leads from the front of the stage to the back. Along it, a strange creature with a large head trudges very slowly upstage, as Colin Fowler draws the first somber chords from the the piano. When the stage brightens slightly, you can see that the creature is two men (Dallas McMurray and Aaron Loux), one behind the other and that the large-headed effect is caused by the black hoodie that McMurray wears. Keeping to their narrow path, one of the men slithers down and through the other’s legs; when he stands, the other does the same thing. In serpentine fashion, the two make their way upstage.

![Maile Okamura and Dallas McMurray in Whelm. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu]()

Maile Okamura and Dallas McMurray in Whelm. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

A woman (Maile Okamura) runs to the men and is lifted, which sets off a series of bizarre maneuvers for the three, or two of them, performed with care. At the back of the stage, another woman (Chelsea Acree) walks in barely discernible slow motion across the back of the stage. She wears a widow’s black veil. When the four dance together, they’re almost antic—witchy. But many of the images seem to evoke those definitions of “whelm.” Okamura begins to lean and sag; McMurray circles around her, returning just in time to catch her before she falls. Three of them join spoon-fashion and sink together. Settled between McMurray’s lifted legs, Okamura gazes upward.

![Maile Okamura on Dallas McMurray in Mark Morris's Whelm. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu]()

Maile Okamura on Dallas McMurray in Mark Morris’s Whelm. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Whelm is an eerie morsel, its strangest element another presence. At one side of the stage sits a shape resembling a craggy rock or a miniature mountain. When there’s enough light to see it more clearly, it appears to be covered in black velvet. The dancers—leaping and falling, tangling and staring upward—pay it no mind. For quite a while, I’m convinced that it conceals people and that they will eventually move. I keep checking. No, it remains inert, and I’d rather not imagine what might be under it.

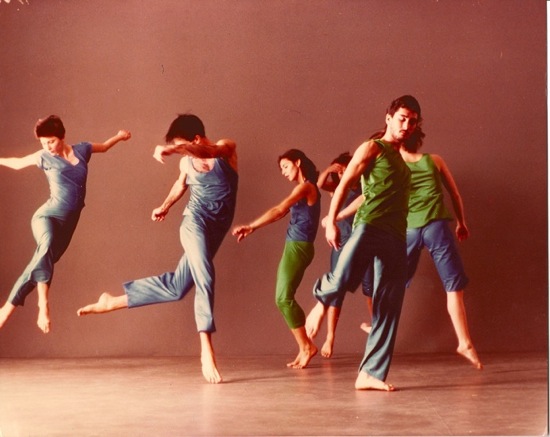

![Mark Morris's Spring, Spring, Spring. Front L to R: Noah Vinson, Laurel Lynch, Aaron Loux, Jenn Weddel, Sam Black, Michelle Yard. Photo: Ken Friedman]()

Mark Morris’s Spring, Spring, Spring. Front L to R: Noah Vinson, Stacy Martorana, Billy Smith, Rita Donahue, Sam Black, Michelle Yard, Brandon Randolph. Photo: Ken Friedman

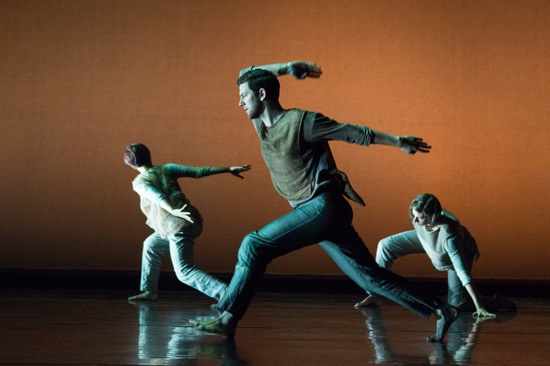

Spring, Spring, Spring is the closing piece on the second of the two programs that MMDG presented at BAM. It begins with a different sort of mystery—a musical one. The audience is sitting in darkness when the first single notes of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring sound. But they vibrate strangely, and when the opening melody breaks free, they have an unusual resonance. A brief muffled thudding also sounds unfamiliar. When lights reveal the musicians, you realize that the members of The Bad Plus (Ethan Iverson, piano; Reid Anderson, bass; and David King, percussion) have not been playing this prelude live; the opening moments of the score had been electronically manipulated and recorded.

The Bad Plus, essentially a jazz trio, isn’t easy to pin down; elements from rock and classicism conspire in its work. The group’s composition is both faithful and innovative in relation to Stravinsky’s score, and the result is terrific. Morris’s ritual is simply dancing to music with allusions to a spring folk festival in imagined open air. The men are bare-chested and wear vividly colored trousers. Kurtzman has dressed the women in lightweight, high-waisted dresses that shade from yellow to pale blue in various ways. Everyone wears a wreath of leaves and flowers. No one gets sacrificed; no one rests for long. Fifteen members of the company form circles and circles within circles. They prance and sway and roll on the ground. They jump over one another. They pair up. They leap.

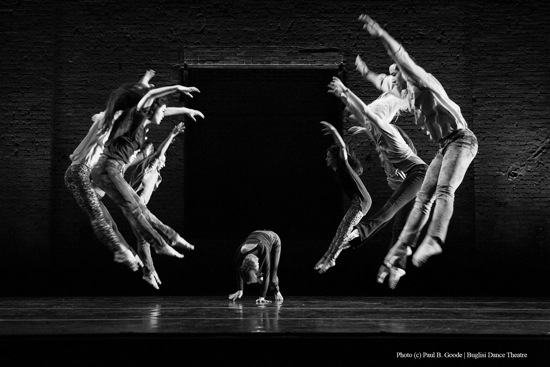

![The Mark Morris Dance Group in Morris's Spring, Spring, Spring. Foreground L to R: Brandon Rudolph, Brian Lawson, Dallas McMurray, Aaron Loux. Photo: Ken Friedman]()

The Mark Morris Dance Group in Morris’s Spring, Spring, Spring. Foreground L to R: Brandon Randolph, Brian Lawson, Dallas McMurray, Aaron Loux. Photo: Ken Friedman

Morris has divided the ensemble into three units: four men, five women, and a sextet of three women and three men. For them, he has woven playful encounters and moments for individuals to shine into a brilliantly patterned celebration that offers only the subtlest of allusions to the Stravinsky-Nijinsky Rite—for instance, in the hint of ritual games and the pairing of men and women. At one point early on, the women in the sextet (Rita Donahue, Michelle Yard, and Laurel Lynch) hold onto their partners (Billy Smith, Sam Black, and Noah Vinson), who lean forward at an angle as they strain to travel; you think of stubborn fields being plowed in a matriarchal farm community. Five women stagger and whirl about, and you think they might have had too much elderflower wine.

In harmony with the music that some of us know so well, people leap boisterously across the stage and exit. Lauren Grant whirls onto the stage and as quickly whirls out of sight. Donahue, on the other hand, balances for a long time on the ball of one foot. McMurray has a buoyant solo, Lynch another one. Together they form chains and indulge in bouts of counterpoint. Philip Watson’s lighting sets them against a blue sky and unobtrusively turns the light golden, dims it to late afternoon, or boosts it to noon.

![Couples in Spring, Spring, Spring. L to R: Michelle Yard with Sam Black, Jenn Wedel with Noah Vinson. Photo: Ken Friedman]()

Couples in Spring, Spring, Spring. L to R: Michelle Yard with Sam Black, Stacy Martorana with Noah Vinson. Photo: Ken Friedman

One of the most memorable sequences appears as the music is building toward the climactic sacrifice Stravinsky intended. The dancers gather in three shoulder-to-shoulder lines, set one behind the other, as in high-school yearbook photos. The people in the front line, say, may lift their linked hands to form arches for those behind them to thrust partly through and then retreat.

You see clasped hands in the second line lifting to come over the heads of those in front, and lifting again to return to position. The effect is of a very human machine, putting out immense concerted energy, seeming to grinding its wheels, yet moving inexorably forward. People break the formation but return to it. Women are lifted, passed down the line. When the music, as I recall, reaches the explosive shouts that accompany the sacrificial maiden’s jumps, they all jump.

There’s no violence in Spring, Spring, Spring. Given the costumes, it’s easy to view the dancers as San Francisco flower children of the late 1960’s, but these are no iconoclasts; they’re controlled in their patterns, expert in their dancing—even in the way they sink down at the end in what’s obviously an avoidance of climax on Morris’s part. Here’s the soft young grass, they seem to be saying. Let’s take a break.

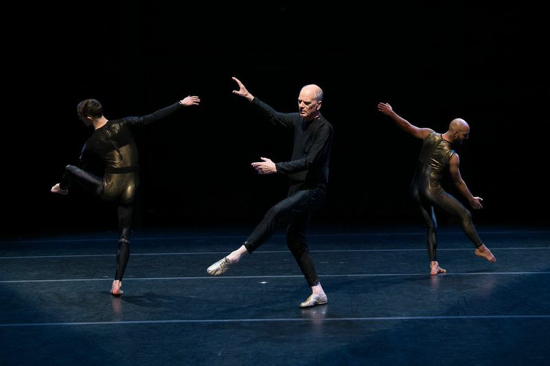

![Mark Morris's Grand Duo. Foreground: Sam Black and Lauren Grant; at back: Rita Donahue. Photo: Erin Baiano]()

Mark Morris’s Grand Duo. Foreground: Sam Black and Lauren Grant; at back: Jenn Weddel. Photo: Erin Baiano

Program A closed with Morris’s great Grand Duo of 1993, set to Lou Harrison’s Grand Duo for Violin and Piano. It too suggests a primal gathering, but it’s fiercer and wilder than Spring, Spring, Spring. In their satin costumes by Susan Ruddie and in Michael Chybowski’s lighting, the dancers ride Harrison’s music (splendidly played by Fowler and Georgy Valtchev of the MMDG Musical Ensemble) as if they’re striving for individuality and companionship in a driven and dissonant society, impelled by the music to congregate. You see Lynch slowly raise her arms to dabble her hands in a mysterious horizontal beam of light, watch her slowly merge into a partnership with Domingo Estrada, Jr. Donahue falls to the floor and rises with her hands folded into fists. Okamura crawls onto the stage and reaches up, as if to push heavy air that’s descending on her. There are almost always squads and crowds coming and going.

But for “Polka,” the last of four sections, the fourteen dancers form a big circle, and for over four minutes perform a fierce communal ceremony—running around the circle with a limping step, thrusting their arms into the air. Feet wide apart and stepping rhythmically, they slap their hips. Hunkered down and facing into the center of the circle, they flick a foot out, then the other. They shake their heads vigorously. Harrison’s music makes one think of the open spaces of the American West and fierce tribal gatherings in relation to a more urban society. It’s significant that for this section, the dancers have changed clothes, in order to be dressed for action—their legs free to stamp the ground and kick the air.

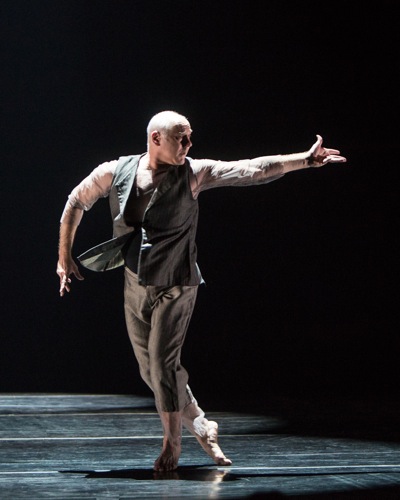

![L to R: Domingo Estrada, Jr., Dallas McMurray, and Aaron Loux in Mark Morris's Pacific. Photo: Hilary Schwab]()

L to R: Domingo Estrada, Jr., Dallas McMurray, and Aaron Loux in Mark Morris’s Pacific. Photo: Hilary Schwab

In its two programs on BAM’s Howard Gilman Opera House, MMDG presented seven works on the stage, all of them marvelously performed by this most musical assemblage of dancers. Morris choreographed Pacific for the San Francisco Ballet in 1995, and Tina Fehlandt staged it for his own company just this year). It’s set to the third and fourth movements of Harrison’s Trio for Violin, Cello, and Piano (played at BAM by Valtchev, Fowler, and cellist Wolfram Koessel). Think Pacific ocean breezes, think peaceful. The women’s long dresses and the men’s long, full skirts (costumes by Martin Pakledinaz) swirl in the gusts of movement.

It’s a delight to see this piece performed by Morris’s own dancers. No one stops to freeze a classical pose. You want feet beating together in the air, pirouettes, arabesques? They abound, and the dancers accomplish them with brio, but they also breath into them and out of them as if they were simple exclamations of good health and happiness. Since this ballet opened the first program, it was the one in which certain dancers began to draw my eyes. All the company members are terrific, but sometimes one or another will appear to have blossomed in some way. This season, two of the men struck me. Dallas McMurray has been a part of MMDG since 2007, and he’s always been fine, but his dancing seems to me to have a new fullness, a controlled abandon. Estrada joined the company in 2009, and I’ve never seen him as vibrant and technically accomplished as he is now. Watching these two was like seeing someone you thought you knew reveal more about themselves.

Sam Black took on a new challenge: replacing Spencer Ramirez in the 2013 duet Jenn and Spencer (Brandon Randolph also took on the male role, but at a performance I didn’t see). In this moving duet, the man and woman embrace, sustain each other, argue, and struggle together, the changes in their relationship in tune with those sustained by the instruments that play Henry Cowell’s Suite for Violin and Piano. In six short movements, a love affair (or a marriage) unfolds, seizes up, and is tersely ended (for now) with a slap. Black performs the male role excellently and I expect will get into it even more deeply over time. Jenn Weddel has ripened magnificently in the part made for her and discovered more nuances. The long skirt of her satin evening gown is not only an unruliness that has to be mastered, but seems almost a part of her, like a lioness’s lashing tail.

![L to R: Laurel Lynch, Chelsea Acree, and Stacy Martorano capture Brian Lawson. Photo: Elaine Mayson]()

L to R: Crosswalk: Laurel Lynch, Chelsea Acree, and Stacy Martorana capture Billy Smith. Photo: Elaine Mayson

Seeing works more than once means more than as well relishing favorite moments, you may notice details of choreography you missed the first time. Watching Jenn and Spencer this time, I saw how the act of the two people clasping hands (one each) on a high diagonal could mean different things—from cementing an agreement to blocking one. I loved re-visiting the crazy episode in Morris’s 2013 Crosswalk in which Acree and Lynch grab Vinson’s hands, and you can’t tell who’s pulling whom. It’s not even clear that he’s the boss when he follows the two of them, who are heading forward on their hands and feet, as awkward and gangling as newborn calves. Also, the first time I saw this piece that Morris set to Carl Maria von Weber’s Grand Duo Concertant for clarinet and piano (played at BAM by Fowler and Todd Palmer), I failed to absorb the full impact of a racing, knocking-down dance that has a cast of eight men and only three women (Stacy Martorano is the third). Nor did I notice the irony of a passage for the men that made them appear—in a highly stylized way—as if they had hold of reins and were urging their horses on.

(You can read my more detailed responses to these two 2013 works at: http://www.artsjournal.com/dancebeat/2013/04/for-eyes-and-ears/.)

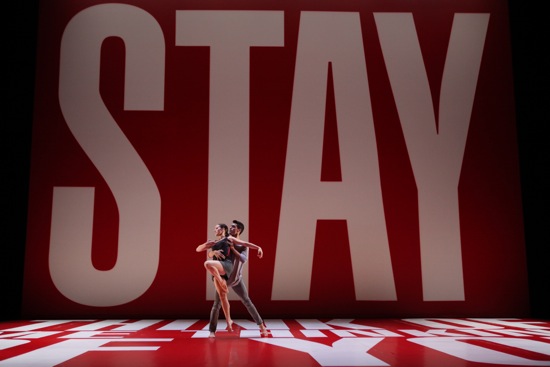

![Mark Morris's Words: Aaron Loux (L) and Brandon Randolph. Photo: Ani Collier]()

Mark Morris’s Words: Aaron Loux (L) and Brandon Randolph. Photo: Ani Collier

When I saw Words in October, 2014 at New York City Center’s Fall for Dance season, I was tickled by the way Morris got dancers on and off the stage. Two dancers holding a rectangle of cloth walk onstage, dropping off performers partly concealed behind the cloth and picking up other.

(You can read my first response to Words at: http://www.artsjournal.com/dancebeat/2014/10/everybody-fall-for-dance/.)

This time, at BAM, I found this device to be even wittier than I had thought. For instance, you may see four pairs of legs walking behind the curtain, but only one person stays onstage, and no one new is taken away. So the device (borrowed from India’s Kathakali theater) takes on the image of a bus; not everyone’s getting off at this stop. It’s also interesting that—although there’s a great deal of vigorous activity in this dance set to Felix Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words—the various duets often occur in a relatively confined space, as if to suggest that these are conversations, even though no one talks.

In all the pieces shown at BAM, it’s fascinating to see, once again, how musical these dancers are (please include Lesley Garrison and Brian Lawson) and how dance-sensitive the musicians. And, of course, it’s Morris who finds inventive ways to bring them together. For our delight.