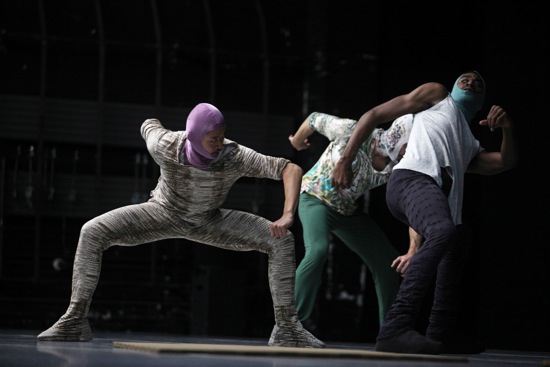

Julia Eichten (L) and Amanda Wells of the L.A. Dance Project in Merce Cunningham’s Winterbranch (without makeup). Photo: Stephanie Berger

A choreographer who has just formed his own small company must be very, very brave to make Merce Cunningham’s 1964 Winterbranch the centerpiece of its debut program. Benjamin Millepied is certifiably brave. Starting a group in Los Angeles and naming it the L.A. Dance Project is already adventurous. I’m an Angeleno by birth, with the scent of eucalyptus and Pacific salt air embedded in my environmental DNA, and though the city’s cultural profile has soared in recent decades, I know that live performance isn’t a major component of what one once could call “celluloid city.”

Millepied first showed his choreography in 2001, the same year that he was promoted to the rank of principal dancer at the New York City Ballet. He’s been adventurous and ambitious from the get go. So, Winterbranch. I remember sitting in the New York State Theater in 1965, back when the dance was fairly new, feeling that La Monte Young’s score, Two Sounds, had skewered my brain, immobilizing me in my seat. A huge Klieg lamp intermittently blazed into the audience’s eyes. There were boos and bravos, outrage and thrill.

On the program that L.A. Dance Project brought to Montclair University’s intrepid, high-quality Peak Performances series from October 25th through 28th, Cunningham’s splendidly daring work was framed by Millepied’s own new Moving Parts and William Forsythe’s 1993 Quintett. The Alexander Kasser Theater was full on opening night. No one walked out on Winterbranch, no one booed, and the applause was prolonged, if not vociferous. Heavy metal has perhaps increased our tolerance for overamplification (the Kasser Theater’s volume was at the current legal max, but that may be relatively restrained). And it was a few years after Winterbranch’s premiere, New Yorkers started going to places like the Electric Circus to experience hallucinogenic interplays of light and darkness.

As staged for the L.A. Dance Project by ex-Cunningham dancer Jennifer Goggans, assisted by Robert Swinston, with Robert Rauschenberg’s original lighting as reimagined by Beverly Emmons, Winterbranch is still a profoundly disorienting piece. Rauschenberg—who in 1964 was not only Cunningham’s resident designer but traveled with the company as a stage technician—made different choices about the lighting at every performance (elements of chance and random selection played a role in the process). Cunningham had requested a nighttime ambiance: “night as it is in our time with automobiles on highways, and flashlights in faces, and the eyes being deceived about shapes by the way lights hit them.” (Cunningham in his 1968 Changes: Notes on Choreography).

The L.A. Dance Project’s lighting designer, Roderick Murray, gives us that for sure. Nothing beams at the audience (John Cage and Jasper Johns had disliked that aggressive element in lighting expert Thomas Skelton’s 1965 chance-determined effects), but lights flash on and off, as if mistaking their cue. From high up on stage right, a bright ray occasionally moves across the stage the way a car’s headlights on a rarely trafficked road might pass your window. Other streaks of light wander too. You strain to see what’s happening in the darkness or in a faint glow or just outside a bright pool. In the opening sequence, a man wearing dark clothes squirms all the way across the stage; the only light flickering on him may come from a flashlight he’s holding.

Who is this man? It’s impossible to be sure. The dancers are Frances Chiaverini, Julia Eichten, Charlie Hodges, Morgan Lugo, Nathan Makolandra, and Amanda Wells. A few seconds later, Wells is visible, standing stage right, holding her arms above her head. She’s wearing dark sweats, and there are black smudges under her eyes like those football players sport to counteract glare. Slowly she lowers her arms. Two men enter with a piece of beige cloth and spread it on the floor beside her. She falls on it. They carry the blanket with her slung in it to the other side of the stage and set it down. She gets up and goes away.

For a long time, everything happens in silence. Someone is carried on. Someone is hauled away on a piece of cloth. Another “car” passes. Young’s score starts its ferocious noise (one sound, says the program, created by “ashtrays scraped against a mirror, the other by pieces of wood rubbed against a Chinese gong”). Hodges and Wells are discovered in a pose—he lying on his belly with his head toward the audience, propped up on his elbows like a sphinx, she reclining across him on her side, resting part on her weight on one hand. Both stare toward us. He pushes and rolls in such a way that he seems to be tipping her toward her feet and folding her up. Then they’re in darkness. A second or so later, they’re back in their pose.

At one point, a mysterious object is pulled across the stage on a rope. Rauschenberg was accustomed to make this out of whatever he found backstage, and Murray’s version rolls along, blinking a red light and festooned with I don’t know what (a broom, a pail, a. . . ?). It’s faintly comical, faintly ominous. In fact, all the images that you can see or half see have a violent edge to them. Eichten and Hodges grasping hands and spinning each other. All six dancers rushing onstage in pairs and whirling down to the floor. Five people in a clump that gradually moves toward the stage’s down left corner, collapsing and recovering as it goes (when the five reach their destination, Wells walks on and dumps a load of cloths on top of them. They crawl off). The piece is even darker than I remembered; you can’t be sure what’s happening in the shadows.

Of all the explanations that people offered to Cunningham at one time or another as to the meaning of Winterbranch, he most appreciated the remark by a sea captain’s wife that the dance made her think of a shipwreck.

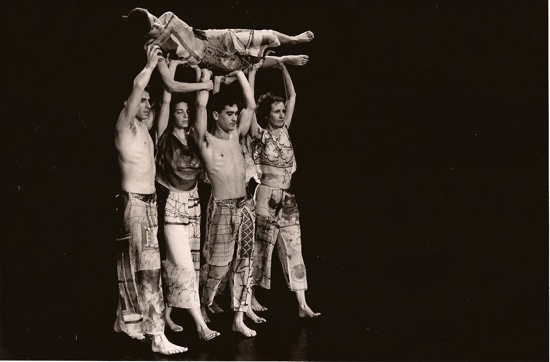

(L to R) Nathan Makolandra, Morgan Lugo, and (aloft) Charlie Hodges in Benjamin Millepied’s Moving Parts. Photo: Stephanie Berger

It was intelligent of Millepied to program his own new work, Moving Parts, first. It’s lighter in every way than the two masterworks, and it introduces the company members you’re going to grow to love. The title doesn’t refer only to the dancers’ bodies; Christopher Wool’s “visual installation” consists of three large panels that the performers wheel into different configurations. These bear black letters and numbers of various sizes set in pleasingly geometrical designs. The costumes are less pleasing—black unitards by Kate and Laura Mulleavy of Rodarte, with appliqués of wide yellow, red, or light blue banding. At the Kasser, Nico Muhly’s very effective score was played by composer at the organ (recorded), Hideaki Aomori on clarinet, and Michi Wiancko on violin—both seated at one side of the stage. Murray supplied the fine lighting.

The mood is upbeat and the dancers cheerful. Their verve helps hold the piece together; although Moving Parts has attractive moments and patterns, it seems to run on a kind of nervous energy, avoiding accumulating and developing its ideas. The movement struck me as atypical of Millepied. Anyone expecting ballet might have been surprised. He could almost have been channeling shreds of post-Trisha Brown ideas. Many of the steps are loose and twisty and flung out; the dancers spend a lot of time on the floor. It crossed my mind that he might have drawn ideas from Wool’s painted designs, but if so, that’s not clear.

The screens swoop around often, and it’s entertaining to see dancers disappear behind them and reappear elsewhere, but the movement doesn’t make statements related to the various spatial configurations, and the dance of the screens increases the illusion of the choreography as busy and aimless (I get the impression that Millepied was deliberately avoiding repetition). When I think back on Moving Parts, only a few images stick in my mind—such as dancers running linked together or three men at vigorous play.

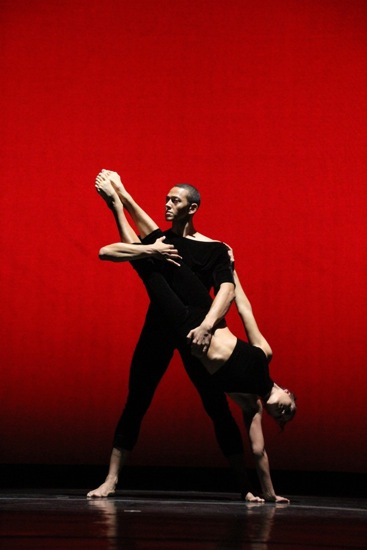

(L to R) Eichten, Chiaverini, Lugo, Makolandra in William Forsythe’s Quintett. Photo: Stephanie Berger

If individual dancers remain part of a mysterious and somehow threatened tribe in the elegantly apocalyptic world of Cunningham’s Winterbranch, they become heroic adepts in William Forsythe’s Quintett, the program’s brilliant closing work. Forsythe staged it for L.A. Dance Project, along with three of the original five collaborating performers: Stephen Galloway, Thomas McManus, and Jone San Martin (the other two were Dana Caspersen and Jacopo Godani).

Forsythe created Quintett in 1993, when his wife, dancer Tracy-Kai Meier-Forsythe, was dying of cancer (she passed away in February, 1994). It honors her in a tone that is both fierce and quiet. This is partly due to its accompaniment, Gavin Bryars’s haunting Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet—the endless, heart-breaking loop of an indigent man’s frail old voice singing the first lines of the titular hymn over a subtly evolving orchestral accompaniment. The music begins faintly, seeming to come from far away, perhaps as if the five dancers onstage at the opening were hearing in their heads. By the end of Quintett, it’s fully present.

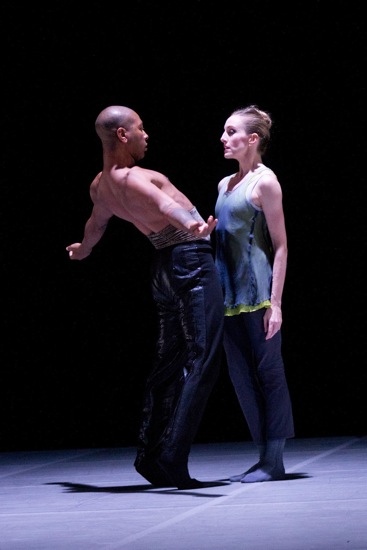

Frances Chiaverini, Nathan Makolandra, and Quintett‘s mysterious piece of equipment. Photo: Stephanie Berger

Galloway designed such different outfits for the dancers that you might imagine that the costumes allude to various other dances of Forsythe’s. Some are simple, others quite extreme. For instance, Chiaverini (who alternates with Wells in this piece) wears a very short, full, orange shift over flesh-colored tights that give the illusion of nakedness, while Hodges wears trousers, a fancily jeweled, semi-transparent blue tee shirt, and eyeglasses. Forsythe’s lighting includes banks of white overhead lamps.

Forsythe conceived this beautiful work as a love letter to his wife—a testament to her strength and her courage (at times, Chiaverini seems to embody her spirit). His style, as always, presents a dancer in motion as a complicated conversation among body parts—arm with head with foot, knee with hips, flashing leg with rolling shoulder. This can look kinky, a bit perverse (Hodges has a tiny solo in that vein). But Forsythian choreography can also turn dancers into creatures of silk or softening wax; sometimes they gather themselves into a ballet move or pose, then stretch it toward asymmetry or imbalance until it slips into something entirely different and finds kinship with that. The mood varies. Lugo attacks a solo as of he’s suddenly coming apart. In a brief trio for him, Eichten, and Hodges, Hodges perches on Lugo’s thigh and gets a swift smack on the butt to dislodge him.

In the beginning, with everyone on stage moving independently, Makolandra goes to the center and delivers a phrase of dancing that will appear later as a kind of motif. He’s tall and slender, and when he bends smoothly forward from the hips and stretches one long arm out, it’s like a grave proclamation “This is it—no more and no less than everything.” Even if you didn’t know the history of Quintett, you’d sense that you were watching a marathon of sorts—dance as life competing against passing time. The performers’ superb intelligence, flexibility, strength, sensitivity, and endurance are juxtaposed to moments of stillness, of stumbling, of falling, of departing. They watch one another, as if needing to keep track of everything that’s happening.

In the end, the large, mysterious object that’s been sitting onstage looking like some formidable piece of radiological equipment projects a small parade of clouds that travels across the theater’s back wall.

Millepied works with what he terms a “Curatorial Collective.” It’s composed of Muhly, Charles Fabius, Dimitri Chamblas, and Matthieu Humery—the last three experienced in aspects of producing in the fields of visual arts, music, and dance. This sounds like a good idea, and Millepied is currently fielding a number of different projects. He also has gained support in his adopted city. Moving Parts was commissioned by Glorya Kaufman Presents Dance at the Music Center, Los Angeles.

It’ll be interesting to see what the L.A. Dance Project tackles next, whether any of the dancers will choreograph for their peers, and how Millepied will hone his own craft to fit the wonderfully gifted group he has assembled.